Nessa’s Blog

The serial diarist

It is done. Roughly nine months after I started, I just now finished re-reading all of my personal diaries, spanning across 22 years, 87 books and 15,508 pages, predominantly handwritten. Over the course of more than two decades, I went through all of high school and uni, several relationships and questionable encounters, worked more than twelve different jobs and, amongst other random events, built a tiny house, appeared on stage with Renée Fleming, published two novels, won a YouTube talent award and traveled all the way to Hawaii to meet up with strangers to celebrate ten years of LOST. I also had an organ removed, went through two rounds of therapy, abandoned my Master’s in philosophy, got in a car crash and had a divorce.

Even before I started to be consistent with journaling (pretty much over night in late 2003), I kept small diaries during vacations as a child. Writing had always been my way of processing things as well as my artistic outlet. There are countless little stories, poems, illustrated ‘books’ (already printed-on paper I stapled together to mimic the look) from that time before I later switched to novel writing.

Because I started so early, there is no way I can imagine my life without the written documentation I have always had. Early on I began to make digital copies of my diaries in case something happened to them, and in those folders I would also collect all photographs, personal e-mails and other documents, tagged by content and sorted by date and time. This collection currently holds about 24,000 files. In short, I have a full archive about my life. I can search for people by their name and the visual differences of the individual books always helped me remember what year something happened.

My obsession with documentation, which later morphed into videography and ultimately into my YouTube career, has had a profound impact on my life. My perception of the past, as I’ve often found, is different to that of many other people. Everything seems very synchronous to me most of the time. It feels like I can just stretch out my hand and the past is still there, along with everyone I knew then and don’t know now.

My archive has been compared to a Sherlock Holmes memory palace. Whenever people hear about my diary habits, they usually express some level of regret that they haven’t ever been able to keep up a routine. (There are also those who shrug and say, ‘I wouldn’t know what to write’ - well …) If you look at the number of smart phone pictures an average person takes, it’s clear that we are pretty keen on keeping memories (and pretty bad at executing that wish - most photos will never be looked at again). We do want to remember our lives. Or do we? Because, as it turns out, having everything that’s ever happened to you right in front of you like that has surprisingly complex effects. Ladies and gentlemen, here’s what I learnt from twenty plus years of journaling.

The narrative trap.

A routine as consistent as this one has a life of its own. Over time you develop your own language and way of storytelling in your diaries, even if it’s your life and your goal isn’t to fictionalize it. When you write it all down, thoughts, events, desires, and you don’t intend on burning the book eventually, you kind of feel that this is in fact an ongoing story. A real one, yes, but a story nonetheless, and you’re rooting for yourself, the hero. You are aware that some things you did were bad choices and didn’t serve you, so you try to reframe them in some way.

There are a thousand ways to talk about certain events in a diary - or to not talk about them. I have found that the way I choose to verbalize what was going on did also affect my actual memory of the situation later on, especially if I read the diary again later. We form narratives about our lives, whether we talk to other people or to our journals, and we like to keep things consistent. And while you might forget what you told your friend the other week and therefore have the chance to come clean, I always felt that my overall narrative in my diaries was more present in my mind and there was a certain pressure inside of me to live up to it. To the version of myself I wanted to be. The one who makes reasonable choices. The one who doesn’t end up in exploitative situations.

The desire to keep being that person has sometimes come into conflict with what actually happened, which is why, for instance, I had subconsciously left out crucial bits in one particular entry, which could have easily identified what happened as sexual assault. I only came to terms with that more than ten years later. In other words: Re-reading your diaries also means filling in the blanks. It’s not an accurate representation of your personal history, even though it can be close to that. It’s the story you are willing to tell yourself about your life at that given moment, and it changes over time.

I am a walking contradiction.

Not only will 15,000 pages of diary inevitably be littered with embarrassing opinion on topics you wouldn’t know the first thing about, I was also confronted with the fact that I have changed my mind about questions of style, politics, social relations and preferred housing at least twenty times, sometimes without even realizing. Amplified by my mix of single-minded autism and frayed ADD, I might score higher on this than some of you, but still - whatever it is we strongly believe in today, there is a good chance that it will feel outdated two weeks later. And that, unless we keep a diary, we won’t even notice that we used to feel differently about it. Most of our actions will contradict what we said five or ten years ago, because now we know better. Which in turn means that whoever we are right in this moment will usually be outdated too, in a while. It’s strange to know that. To know that some of what I currently want and care about will be irrelevant to me down the line. I’ve found that once I accepted that more, I was obsessing less about the outcome of things and didn’t take myself too serious anymore - in a good way. Tomorrow is a different day either way.

The gift of forgetting

It takes a lot of personal stability and awareness to be reading through years and years of personal reports on friendships, dubious projects and mental breakdowns without coming to the conclusion that you, as a human being, fundamentally suck. All your failures, all your prejudices, your illusions and your brave obstinacies will come to light (if you’ve been somewhat honest in your diary in the first place). It’s every therapist’s gold mine - but without a therapist, you might sometimes feel like you’re not really doing so well in life.

The truth is, most people forget most things they’ve ever done, and they’re pretty good at hindsight-contextualizing it into an elaborate and reasonable construct to cover up any potential embarrassment. Instead of dealing with the fact that we all make many, many ‘mistakes’ along the way (aka go through necessary learning processes), it’s more socially acceptable to shush about them. Not so the diary-keeper who, in her bold endeavor to document her courageous fights against injustice and ignorance in the hoi polloi, couldn’t help but accidentally also document how wrong she was about most of those things. All of this in written form, forever imprinted onto the patient pages of a fancy notebook.

I have rarely considered throwing any of my diaries away, ripping out pages or otherwise deleting evidence of my own ‘shortcomings’. In fact, there is this vague idea that parts of them will be published posthumously and people can take away from them what they want. But sometimes, just sometimes, I imagine setting a huge campfire somewhere and burning them. I love my memories, and yet there is a strange burden in them too. You can’t escape your past quite so easily, and I think sometimes you deserve that chance. We take who we are with us, but we’re not required to take all of it, everywhere, at all times. Some of the events that I clearly remember because I’ve written them down are already forgotten by everyone else who was a part of it. It’s sad sometimes - but also relieving.

Mind you, forgetting is not the same as ignoring. What’s there is there, and there are things in life that will always play a role, no matter how long ago they happened or how hard someone is trying to deny that they did. But neither do I have to remember every single time I have been humiliated by other people, nor do I have to remember all horrifying details of months of living with ME/CFS. It’s okay to let these memories fade over time. And I guess the same goes for the good things - because you can’t bring them back and comparing them to what is now doesn’t help either. Outside of this marathon re-read, which I won’t be doing again any time soon, I now mostly try to engage with my memories as they come up. It can be physically and emotionally overwhelming to reactivate all of them over such a short period of time and I actually had to take regular breaks to let the emotions play out. The body can’t handle everything at once. Thus, forgetting is part of the process.

Immersion

Lastly, I want to emphasize one thing. Even after practicing on well over 15,000 pages, I have found it impossible to accurately capture any given moment in time in writing, in photos or otherwise. Human memory with all its sensory input is way more complex than that. Diaries help a great deal, but ultimately, in order to truly remember, we have to be present in the moment. The less distracted and dissociated we are, the more immersive the experience. There has been a lot of talk about the experiencing vs. the remembering self. If you want to hear my opinion as a serial diarist, I’d say that as long as you put aside enough time regularly to sort through what happened, whether that’s through journaling or other rituals, the goal should always be to experience. Memories are incredibly precious to me, but ironically, in their fleeting way despite all my documentation, they also prove that life consists not of preserving the past but of shaping and discovering the present. When I look back on those 22 years, it’s … a lot. I feel like I have made use of every possible moment of my life in some way. And that’s a legacy I want to live up to in the now. Which is not to say, do something crazy every day. Actually, I’m looking for more peace in life than I used to. But whatever it is that I choose to do that day, I want to do my best to be present for it in all its complexity. Living is now. Remembering can come later.

Read this: Great art by bad people and the comfort of things

Hello again. As promised, I will continue sharing what I’m reading and watching, every now and then. There is too much good stuff out there (even with all the nonsense) and I figured that word of mouth still counts as something these days if we don’t want our recommendations to be ruled by the few companies who can pay enough for Google AdSense. So here we go.

Monsters. What Do We Do With Great Art By Bad People? by Claire Dederer

The art vs. the artist battle is as old as art itself - and it’s not just about art. Are we allowed to appreciate something even if we know the person who made it has afflicted suffering unto others, sometimes repeatedly? The issue is complex and an apt discussion in our times. Something we have to come to terms with, sometimes multiple times a day, as we choose which movies to watch, which books to read, which politicians to listen to. Initially I was unsure if the memoir style of the book was what I was expecting out of the topic, but Claire Dederer convinced me. It is, in the end, a deeply personal question, and her contribution to it is meaningful, well-written und doesn’t lack humor, fortunately. No moral high grounds here, I swear.

The Battles of Tolkien by David Day

Saying that you’re a Tolkien fan and then only having read the Lord of the Rings (and possibly even without the appendices, gasp) is kind of like calling yourself a chef and only making one dish, ever. The world Tolkien created is vast and full of references to real-world mythologies, something which I only fully learned to appreciate once I started to read books about Tolkien, aside from everything he has written himself. The Battles of Tolkien is one in a larger collection of monographies by David Day, focusing on different aspects of Tolkien’s creations. The books are beautifully illustrated by many different artists and the binding itself is decent too. It is worth pointing out that David Day is not officially affiliated with the Tolkien Society and has been criticized for some of the details he’s been including in his dictionaries, for instance. But as with each book I read, I take things with a grain of salt anyway. This read was definitely worth it and the books have been a global success ever since they came out.

The Comfort of Things by Daniel Miller

In 2008, Daniel Miller and his research partner did something a lot of people would like to do but, for social norms, can’t usually - they went along a London street and basically looked into people’s homes and asked questions about their stuff (with their permission obviously). This resulted in a lot of material for anthropological research, as well as in this book, which portrays thirty of those houses they visited, whether they were inhabited by singles or families, stuffed with memories or eerily empty. This unusual book teaches you a lot about people, their relationship to their belongings and the way life goes. With all of its real-life stories about heartbreak, immigration, family bliss and personal quirks, this book is as authentic as it gets. Loved it.

In other news, I am doing well - I’m working on my psychology degree (two thirds officially done now), planning for the imminent future (will hopefully be able to give an update in a few weeks) and finishing up my full re-read of all of my diaries in consecutive order (15.000 pages, chrm). More on that maybe in a little bit, since keeping a diary for more than two decades at this point has taught me a thing or two as well. See you around.

Ballad of the misfit

The year has started out marvelous and then turned into a bit of a drag recently - I’m in the middle of a big life change so naturally, my nervous system is sensitive and loneliness and every day life chores are more exhausting than usual. I decided to brave the cold (and the desire to just stay at home) and go out with one of my closest friends on Thursday. We ended up in an indoor market among spices, Italian delicatessen and fluffy pastries. It was glorious, despite my headache. On the way back to the station and having trusted our intuition to guide us through the stalls and the maze of the streets of Stuttgart, we wound up in a book store where, naturally, I walked straight up to the English section. As I browsed the paperbacks, I almost immediately picked out Jenny Mustard’s new novel What A Time To Be Alive.

In case you’re unfamiliar, Jenny is what me, a late bloomer on the platform, would call an OG YouTuber. You know, one of the ones who were there when it began (her channel was created in 2014, which, if you think about it, is really not that long ago), who were successful, who were somehow larger than life. Being a writer myself, I remember how I grinned when I chanced upon her first novel Okay Days in a local book store a few years back and thought, good for you! Someone from my niche making it in the big world out there. So when I saw her second book now, I just went with it.

I didn’t know what I was expecting, but I certainly wasn’t prepared for the revelation it turned out to be. This is not a book review and I’m not going to spoil the experience for you either, but I will say that the way she described this young woman going through the motions as she is struggling with university, romance and friendships as a twenty-one year-old, I felt understood in a very rare way. Whether it was intentional or not (it’s not mentioned anywhere specifically), Jenny described what I’m assuming many neurodivergent women will be familiar with. The awkwardness of being around other people, even when you’re familiar with them and have somehow figured out how socializing works (and people actually deem you pretty good at it). The internal struggles of over and under attaching to others, overanalyzing people’s actions towards you while underestimating the need for your own boundaries. Carrying the burden of being a life-long misfit while, paradoxically, now often being seen as interesting, inspiring, socially adept.

Especially the last bit. It’s been interesting seeing this dichotomy play out in my own life. While I was away over the holidays, in a hotel by myself but also surrounded by strangers constantly, quite a few people walked up to me and started a conversation, and I, too, would sometimes initiate contact by giving up a seat at my table or simply offering to take a picture of a family, make a humorous remark or whatever came to mind. People would then often comment how outgoing, communicative and radiant I seemed to be. As if I was somehow in my natural habitat.

This is interesting because none of this came naturally to me in life. Like, at all. If you go back and watch old camera footage of myself as a child, how I engage with other people, and if you read my diaries from my childhood, you will quickly see that otherness in me that got picked on in school. I used to describe myself as a robot or an android, and it’s easy to see why. My posture was rigid, sometimes even distorted. I had a hard time easing up with people my age because I had very little in common with them and their unspoken rules were off to me. Secretly, I was envisioning a different environment for myself - a mixture of academia and the world of movies - where I believed I would fit in more. To prepare for this initiation, whenever it would happen, I practiced the poise and speech of my role models on screen while being at a loss with the habits of my peers. As Jenny’s protagonist Sickan, I am no stranger to being called ‘strange’, openly and covertly.

Many years later, and because we dedicated so much work to our social skills, both Sickan and me eventually turned our experiences of being ostracized and never really belonging into almost the opposite, at least on the surface. I could now pride myself in being able to blend in with almost any crowd if I so wished, even if that meant that I would sometimes lose myself in the process. Like Jenny’s heroine, I have often found myself waking up with anxiety in the morning because after a night out with others, I felt like I had played a role a little bit. It’s been a solid decade of trying to find a balance there, and I’ve made progress.

The interesting thing about being a misfit is that it creates a very interesting life story. When you move past adolescence (where normativity still plays much more of a role), people are often intrigued by otherness, especially if by now you’ve learned to show it in a graceful, curated version - less raw and awkward than in your teens. Many, past the age of thirty, forty, fifty, have been disillusioned by some of their own life choices and find it very fascinating to talk to someone who looks at the world differently and has seen a fair bit of trauma and magic without losing their drive. The neurodivergent woman is no longer the circus attraction she used to be, she is now the socialite that people invite over because she’s got stories to tell. And it’s nice like that, because finally she is actually part of the conversation, not just the subject. People actually do listen and she is actually allowed to contribute.

When I look back on my fantasies of being part of a secret academic society of some sorts or becoming best friends with Emma Watson as we brave the intricacies of acting life together, what was obviously behind it was the wish to belong and to be taken seriously. When your experience growing up is that the laughter in the hall might be directed towards you, you don’t take these things for granted. Like Sickan, my nervous system is still often hypervigilant, and not just because of the bullying. Not establishing boundaries for fear of being abandoned or rejected creates many vulnerabilities growing up and you learn to be on your guard while at the same time trying to tell yourself, it’s fine, it’s fine. I’m strong, I can handle anything. It’s this type of determination that helps you practice starting conversations with strangers even though you’d really rather not because you don’t know what you’re doing.

It has become easier to belong in adulthood, I will say that. Not just because there’s less tension than in school between peers, less rivalry. Or because by now, I do know what I’m doing when starting a conversation. I have also started to experience the desire to belong as less absolute, which takes the pressure off, and therefore the inevitable disappointment when, after long conversations with people that feel like bonding, they will get up and leave, returning to their life and keeping you as an inspiring memory, not as a life-long friend. (Which, in most cases, wouldn’t have worked out anyway, but when you’re young and vulnerable, you are also desperate.) And, like Sickan in the novel, I have learned to stand up for myself and gently or firmly remind people that I’m not a prop to them (sorry for the professional pun). Remind myself that true belonging happens not by seamlessly fitting into an existing situation and giving it all you’ve got and more, simply in the high hope that someone will actually see your true self through all of that.

Not too long ago, Emma Watson shared on a podcast how lost and vulnerable she was in early adulthood post the Harry Potter era, where everything had been kind of like a big family. For a long time, I had naturally assumed that she would never struggle to make real friends anywhere, with the gracefulness and openness she exuded. Turns out, she did. And I can only guess that Jenny Mustard’s intimate description of Sickan’s drift in Stockholm is at least partially based on her own experiences - it seems too authentic to be made up entirely. Some things you only know if you know.

The point is: It is precisely this life-long effort of trying to master social norms and relationships that sometimes stands in the way of us ‘others’ finding true belonging. We pride ourselves in finally being able to fit in ‘on demand’ and sometimes forget that in order to be seen for who we are, we can’t simply fulfill perceived expectations. Many of us, whether neurodivergent or not, have turned our misplacement in the world into a source of power. We have used the humiliation and confusion of being odd as fuel to make look effortless what took years of research, therapy or bravely living outside the norms. I am happy to say that life in my thirties as an outsider is a lot easier than in my twenties, and that it is not simply due ‘finally growing up’ (i.e. ‘quit pretending you’re something special’) or some bullshit like that. But I also want to clarify that by ‘easier’, I don’t mean that it ‘just works’. I mean I can now sometimes go to a restaurant with people and actually enjoy it. I no longer get panic attacks when meeting someone indoors. Most of the time. Some social norms and situations I now ‘get’ and actually like, others still stress and exhaust me, no matter what. I regularly get emotionally overwhelmed in supermarkets, for instance. Especially if they play music. I have meaningful friendships. But certainly not ‘just like that’, and my ability to socialize ‘on cue’ actually doesn’t have that much to do with it. I’m not being inauthentic for doing it - I do enjoy it these days. But like you enjoy playing a difficult piece of music on your piano with someone. You are proud of yourself for pulling it off, but there’s much more to you than that and you certainly can’t do it all day, every day.

For a while now, I have suspected that many, many people who end up in the limelight to some degree and stay there voluntarily have had similar social experiences to my own. Because if you can have all the meaningful relationships you want in your life, your desire for parasocial relations through fame and notoriety is maybe a bit more limited. The stress that being a public figure puts on you, you only continue to choose that if there is a desire that’s being fulfilled that you can’t fulfill elsewhere. To be liked from afar once you’ve mastered how to conduct yourself in public is better than the disappointment of being rejected from up close for being awkward. It’s obviously more complex than that, in my case as in that of everyone else, but there is something to it I think.

Meaningful relationships still don’t come easy to me. Just because I have learned social skills and have an online following of some sorts doesn’t mean that my body and the rest of myself have forgotten all the times when things between me and other people went wrong for one reason or the other. In order to learn to how to walk up to people and chat, or make a group laugh, or enter romantic relationships with all their subtle expectations, I also forcefully put myself in situations in the past where people were taking advantage of that vulnerability and eagerness. Which is to say, the world likes people who are outgoing and especially in the day and age of social media, it’s an asset in a way. You look like you made it, like you’re it. But it’s not always worth the price to try and become that, so don’t be fooled, especially not by me. Like Sickan, I’m proud of what I have achieved, but I’m also still bearing the scars I got along the way. And I’m glad we’re starting to talk about that more.

Now go an read Jenny’s book. It’s awesome. (I’m not being paid to say this, she doesn’t even know me.)

Lessons of the past

I hate to be stating the obvious, except in the business of comedy, so I'll keep this short: This is it. 2025 is coming to an end.

For what it's worth, I’m not even entirely convinced it was only one year because there are entire galaxies between how it started and how it's ending, at least for me.

As I‘m pondering this, dressed in a bathing suit and looking out onto the park of the thermal spa I’m staying at (last minute getaway over the holidays), there is a sense of awe and gratitude, mixed with a fair bit of perplexity. Life is great. Life is weird. A lifetime ago (eleven months, to be precise), walking up and down the stairs of my rental to do laundry started to become impossible. Two days ago, I went on a spontaneous 12 km hike with 500 m of elevation in -2°C and a snowstorm and all I got was sore calves.

This marks the final bit of reintroduction. It is now confirmed that I'm able to do everything I could do before I got ME/CFS. I'm also using the sauna again after 15 months and let me tell you, it's awesome. So as I'm looking outside towards the big cascades, the powdered trees (yes, we do have snow here) and the dog walkers with bonnets, I'm also looking inward, trying to make sense of what happened in those twelve months.

Usually, I re-read all of my diary entries of that year towards the end of it. This year, my endeavor was a little bigger. Starting in 2003 when I first picked up journaling, I went through all of my past up to 2019. 12,000 pages (no, it's not a typo), over 70 individual books. Initially, the idea was to catch up all the way to the present, but 2019 and onwards mark some of the toughest years and I had to take it slower.

Nonetheless, 16 years of life is a lot to read through. I had lived in at least seven different homes, depending on how you count, I graduated school and university, abandoned my master's, worked as a journalist, model, videographer, writer, streamer, stage hand, props manager and Youtuber (I probably forgot some), worked my way through challenging relationships and built a tiny house. The remaining years I have yet to read will see the difficult road to my parking spot for said house, my marriage and the falling apart of it, mental health issues, therapy and, eventually, severe illness. It's kind of a lot.

A little over a year ago in one of the more stable phases before the big dip in early 2025, I had tea on the market with a dear friend and one of her friends. As we, all three of us spiritually open to various extents, discussed our relationship with the past, my friend's friend said: ‘The past is a messy kitchen drawer. Why would I want to look in there? I put stuff in it I want to get rid of and that's it.‘

Her view was opposed to pretty much everything I stand for, with the meticulous and sometimes ridiculously ambitious documentation of the past. And yet it got me thinking. The past is messy. Making sense of it is usually a hindsight project, and because memory is unreliable even when you have a diary at hand, your construction of what happened and why can take on many forms; depending on what fits your current narrative about yourself.

I was never going to agree with her statement fully - every single thing we know about resilience, therapeutic success and personal growth tells us that ignoring what happened to you (and a lot happens to all of us) will not work in your favour. But she certainly had a point in reminding me that constantly trying to sort out that one drawer in the kitchen where all the 'umm, whatever, no idea' stuff inevitably lands can be unnecessarily obsessive and take away from the task at hand. Which is, live your life.

I'm writing this entry not only on the back end of an incredibly transformative year, but also a few weeks after I made a big decision that will affect where I live, work, and much more, in the coming years. I'll speak more of it at an appropriate time, but suffice it to say that just like with my illness, this will create a before and after distinction in my life. A massive change.

Just like sorting out a kitchen drawer can become obsessive, so can dealing with the past. In trying to create meaningful story arches and personal continuum you can lose yourself to things that were - but maybe also never quite were the way you remember them. Circling around what was can be the mirror you need in order to see your own destructive patterns - and it can reinforce them by shifting the focus from what could be to what has already happened.

It is the same with labels of any kind. Stickers you apply in hindsight to give structure. I use them too. I call myself neurodivergent, for instance. The danger lies in letting labels and past experiences become the framework for the future. Understandable, in some sense. We are who we are, and accepting our own boundaries is important. But self-limiting prognosis on the basis of applied names and recent history is a common side-effect and something I see a lot in the ME/CFS and neurodivergence bubble (which, not surprisingly, have a big overlap).

Ordo a chao - out of chaos, order. I live and breathe this idea. But structure and, in that, the construction of the past can become self-serving and in turn obstructive. Yes, I want to understand how I got here, also in the hopes of not repeating patterns that led to my sickness in the first place. But I also, for now, just want to be here. And with the big decision I recently made, it became clear that it wasn't necessary for me to have all my kitchen drawers in order before I could move on. Some of them will always be messy. I love structure. But I also love life.

How did I get here? Well, the nervous system works in mysterious ways and I will probably never fully understand what happened, except that trauma therapy and somatic work had a lot to do with it. For now, that's enough. I didn't bring the remaining diaries on my trip (but I did bring a lot of other books). Instead, I simply relish the complex feeling of being on the other side of something big and knowing in my heart that the future will look very different from the past in many ways. The present already does. And I trust that even though there are still chaotic drawers, I can just get on with the cooking. Well, actually not really because I booked a four-course meal tonight, hehe.

Happy holidays, everyone. Pamper yourselves and don't fear the shadows of the past. It's okay to put them in the cupboard for now and maybe sort them out later. More soon.

The best job in the world

Happy Nessa gluing hundreds of books together for a set piece

I attended a 15 year graduation reunion the other week and it was surreal. Not only had most of the sixty or so attendants not seen each other in over a decade, we also collectively beamed and hugged when we arrived, as if we had all been best friends back then. Some clearly hadn’t been - but it simply didn’t matter anymore. Everyone was grown up and lived their life and it was delightful to exchange stories and update my picture of people I’d last seen when they were eighteen years old. It was a great night.

The question everyone prepares for on a night like this is obviously, 'So what do you do?' My reply often started with 'Well ...' and a short pause while trying to figure out how to explain it without needing a diagram. The thing I talked about the most, though, wasn't the tiny house or YouTube, it was my work in props. I might even have described it as ‘the best job in the world’ to someone, and I stand by that.

You, too, will have noticed that I speak about it highly. It’s not the naive excitement of someone new to the job (I’ve been doing it for seven years now, after all), it’s a deep appreciation for a mysterious, sometimes dysfunctional but always fascinating world in which things still run a little differently. Old-school, some would say. Let me finally properly introduce you to the strange microcosm that is a theater and explain why for many of us, stage life is the only life they will ever want.

view from the wings during a ballet performance. Little light, little space - trying not to get in anyone’s way is the priority

To get the basics out of the way: Every major stage production is run by dozens, sometimes hundreds of people in the background. Depending on where it’s happening and what it is, the timespan between the first rehearsal and the final performance can be days, weeks or years - especially for musicals and in repertory companies. I personally am working on projects that run for two weeks up to two months. We mostly do staged operas and ballets, some of which will be guest performances from other companies where we help out more, others will be our own productions where I am now in charge of all props.

Speaking of. There are, like I said, tons of people involved in a production - from dancers to accounting staff. The most common backstage professions are stage tech, lighting, sound, props, hair and make-up, costume and stage management, who runs the entire show and coordinates everything. (By which I mean, everything. I invite you to look at some footage.) All of these professions are invisible during performance. If we ever appear on stage, we will be disguised or in costume to blend in. Unless it’s one of those rare occasions (happened to me once in seven years), we don’t get to participate in bows.

Props are everything that is being used on stage that doesn’t count as costume or part of the set design itself. Often, this is furniture (some houses even have their own department for that) and a combination of all kinds of everyday life objects - jewelry, letters, cameras, flowers, sometimes food and sometimes also weapons. Depending on the production, it is a props manager’s task to manufacture or acquire, alter, repair and handle those props according to the director’s and cast’s needs. There are many things to consider, apart from design and general safety. Some surfaces cause unwanted reflections on stage, some materials are banned because they aren’t fireproof enough. Other times, objects need to have a certain weight or other functions (practical effects, hidden storage). Every production will be different.

Depending on the scale of it, we might spend up to six weeks just preparing props and only use them in four performances altogether. Other times I’ve handled old fabric or paintings that have been around for decades and have seen several hundred shows. Some of the guest performances I’ve worked on have been around since the eighties. Things constantly break and it’s your task to respectfully fix them.

coloring hundreds of fake flowers individually

Despite the sheer number of participants, an opera or ballet production usually feels rather intimate. Everyone I interact with to get my job done is right in the same gigantic room with me - on stage, backstage or somewhere in the workshop. I hardly ever have a situation where arrangements are being made entirely over the phone or e-mail, without ever seeing the person (which is super common in many jobs). If I need to discuss something with my boss, I go to his office, which is just a flight of stairs away. The dancers I need to talk to about the alterations I made to their weapons are in the dance studio and the director I need confirmation from is in the auditorium overseeing rehearsal. Everyone is right there.

And not just that: Everyone is right there all the time. With project-based work like mine, productions don’t stretch out too much. We build the set, we rehearse, we perform. And because of our schedules where no time is wasted, we see each other pretty much all day, every day, for weeks. We have to learn to get along, and because we’re practically in one big room, the mood between two people can quickly escalate to the whole team. Fights happen, of course they do. Surprisingly though, it has been proven time and again that even people who really can’t stand each other are able to work together when it comes to bigger things. If hundreds of others plus a large auditorium depend on you getting your act together, you do it.

The social environment in a theater in general is vastly different from what many people experience in their work life elsewhere. It is shaped not only by the intensity of the rehearsal process and the complexity of running the operation, it is also influenced by the culture around actors, dancers, singers and directors. Everything is - has to be - very hands-on. Like, literally. As an amateur actor, one of the first things you need to learn is to overcome this incredible caution around touching anyone else and showing emotion (obviously, healthy boundaries need to be established, which is a whole other conversation). It is a performer’s job to interact with other people on stage in a very physical kind of way, not just in dance. You will therefore see that the communication off stage, too, includes a lot more of that. There is a whole debate in our culture about touch-starvation and I’ve found that except for a very small number of bad actors (in a secondary sense) out there, the way we’re dealing with touch, which is a natural part of human interaction, is a lot healthier than in the corporate world (where inappropriate behavior is just as common). Everything is a lot heartier. People go out to celebrate after the premier. Many a night has been spent in random hotel bars or restaurants.

When you spend that much time together, something I’d like to call stage humor naturally develops. Lighting rehearsals are prone to rising levels of craziness because if you’re not a light engineer, you have nothing to do than to sit in the dark and wait for your cue - for hours. But also, you can’t run off because the cue might just come while you’re gone. I have personally been taped to a wall with duct tape out of someone else’s boredom. Ten roles of tape have been stacked on my head, with an added banana on top. Someone built an elaborate shrine for a schlager CD next to the stage manager’s desk. There have been Nerf Gun battles (including obstacle courses) and diverted mannequins - I swear I was only gone for a few minutes and they added inappropriate details to the poor guy. There have been attempts on my sanity by a colleague jumping out of the wings with an Anonymous mask on and the way dancers hype each other up while waiting on opposite sides of the stage for their entrance is a game of its own. We laugh a lot.

This obviously also comes from the way a production plays out hormonally. The buildup of (hopefully not too much) stress and anticipation over the course of a few weeks culminates in the excitement of opening night and the rush of emotions when the show has run successfully and you can hear the audience cheer and hoot. Everyone is happy, even if the video installation failed mid-play or the dancers accidentally dunked one of their props in the orchestra pit (musicians are generally not too happy to have a plastic bottle land in their lap while they’re playing). Because you’re performing on-point for a live audience, a flawless performance means much more than a flawless take in film. You have one chance to get it right. It feels meaningful that way.

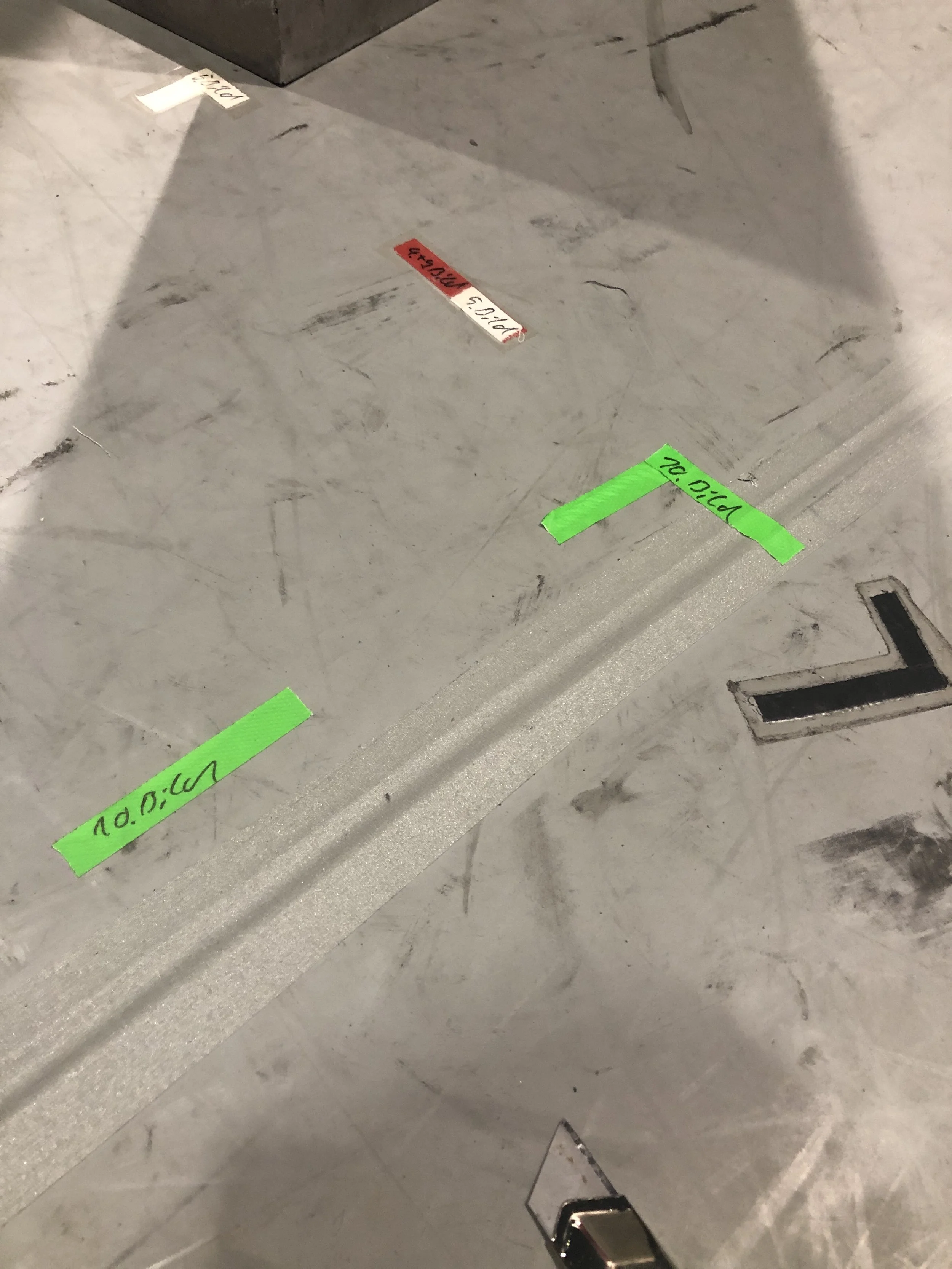

markings on the floor for one of our shows - each piece of furniture or set design has a designated place in each act and we sometimes only have seconds to place it during a quick change

With props, there are a few peculiarities. You quickly learn to improvise because there is no rule book for how to build one hundred pink baby dolls that can be screwed together live on stage as part of the performance. How to hide a water flask in a costume to give the singer a five-second interval to drink during her performance of almost two hours. It’s always new, always different. You have to find your own way - which, again, feels more meaningful. And when it comes to it, your intricate solution either works or it doesn’t. You can’t talk your way out of your responsibility. Sometimes, the whole show depends on a single little mug, candle or necklace. I never have to ask myself: ‘Do I even matter in all this?’ I know I do.

The beauty of all this is that everyone has their role to play but no one carries the responsibility by themselves. Unlike with YouTube, where I am in charge of every single thing and always in the spotlight, I can just be a happy little gear. What we create on stage is bigger than the individual contribution, which is especially helpful on days when things don’t work out. Yes, you were late on the cue but your colleague helped you out and no one out there really noticed. When it comes to it, the team work backstage is unparalleled. During a recent ballet performance, cables got stuck in a fly bar, causing the power supply to a light to fail. It just so happened to be the most important light of the entire show that was due to have its moment in a few minutes. In the dark and while the act was already running, a solution was found amongst our colleagues and no one in the audience was ever the wiser.

As a workplace, the stage is not without its hazards. There is a reason why everyone gets a mandatory briefing before rehearsals start and there is also a reason why our mandatory liability insurances cover up to 10.000.000 Euros of damage. If your actions cause the sprinkler to activate in a room this size with wooden floors and curtains all around, then, well. Also, we’re working with potentially hot lights (by far not all of them are LED), all kinds of fabric (treated, but still) and, sometimes, live fire (candles, cigarettes etc.) on stage - all in the semi-dark with lots of people around. Tons of material are hanging above your head at any given moment. I’ve seen a light drop off the ten meter light bridge. It ain’t pretty. I’m pointing these things out because it adds to the overall sense that you have to be on top of your game when you come to work. Fumbling around with things you don’t know much about or not taking your responsibility seriously can cause other people great harm. What you do backstage matters in many ways. And as much as we all want our work environments to be safe, I always feel like stage life is very representative of the rest of life in this way: action - reaction (please read this with a French accent). I have learned many valuable lessons about that at work and it has actually translated into how I participate in traffic as well.

complex tech everywhere - pluck at the wrong cable and you’re busted

When I mentioned old-school in the beginning, I was referring to all of the above, but most importantly the handling of props itself. I am working with real things and real people. Yes, when managing a new production, I obviously spend time on my computer researching and putting together a database. But once production starts, most of my days are comprised of me actually having physical objects in my hands and actually delivering them somewhere on foot. It’s wild that we have to even say that but this is not a given in many jobs anymore. Props is one of those jobs that you can not ever do remotely. And I love that. The techniques we use to stain, age, repair, intentionally break objects have been around for decades or centuries. Up until recently, there was no formal training for the job (and it’s still not widely adopted). You learned from the people before you. And with the diverse backgrounds that I’ll talk about in a minute, there is always something to learn.

I already had an interest in classical music and ballet before I started this work, so I was especially appreciative of my opportunity to work with some of the most acclaimed artists in the industry. Name-dropping always feels kind of braggy and I already mentioned the Berlin Philharmonics in a previous post, which gives you enough of an idea. What I picked up from the directors, stage designers, conductors and dancers I met along the way has been truly inspiring and influenced my videography and my writing alike. I’ve found that for many of my colleagues, working in this field has opened them up to a much better understanding of music and art. For me, certainly - I used to be very puristic about classical music and ballet. After a few years in the industry, my taste is much broader and at the same time, much more refined.

When we sit together during lunch break or after the hours, we sometimes joke that backstage work is for the people who never got a grip in life. It is certainly a far cry from my initial plan to become a teacher - a steady, full-time job for the state. Now I work from project to project, self-employed, and I certainly make less money. But. What always fascinated me was how many different people come to work for opera and ballet - and how you would never guess that they love it like that. In our team, I am the only former dancer (I trained in ballet for a few years, sometimes up to three times a week) and not everyone is always up to speed with the plot of the opera we’re doing, but the dedication I see in a team so diverse always warms my heart. People from all walks of life, all countries and all social backgrounds come together, and that creates a space of respect and true diversity that I really appreciate. Maybe some of us do struggle to hold down other jobs that are less exciting, maybe some of us have a troubled past. It doesn’t really matter. We’re coming together to create something for the sole purpose of entertainment. We make people have a good time while they’re here. And it unites us when we feel like we have achieved that. Sometimes that’s enough to create a lasting bond.

In many ways, stage life is what I want life to be. It has community, it has real things, high stakes but also beautiful rewards, it has dedication, humor and a natural cycle to it. And it has art - which I have never been closer to than here. Just like anything good, it can be addicting and post production depression is a real thing. But to me, all of that is worth it. I’m not just working somewhere, I have a job to do. A responsibility to fulfill. A community to engage with. For that, I am eternally grateful.

side stage during performance - tons of people, everywhere, all the time

As I was standing there last weekend, explaining my professional situation and knowing full well that my year book had said ‘future profession: teacher and writer’, I grinned to myself. My own excitement got the better of me. I know that some people - not necessarily at the reunion - feel like I have ‘wasted my potential’ by not pursuing a career that makes use of my excellent grades and high achievements. Well. I’ve come to realize that above all, what I spend my time with should feel meaningful and give me a sense of belonging. Backstage work has a beautiful way of giving me that every single day and I hereby officially encourage everyone to look into it. We need good people. It’s never too late.

So now you know about the best job in the world. Well, at least a little bit. I personally think there are many best jobs out there who combine all of these elements - or even more (for instance, I see very little sunlight at work). The point is: They are out there. I never knew about many of them growing up. Thankfully, now I do. And now you do too. I’m writing this while packing my bags - I will be working across the country for a new ballet production next week and I’m excited. Since this has come up quite spontaneously, the next episode on my channel will be delayed a little. In the meantime, take care and please never settle for a job you hate. Peace out.

The shadow of doubt.

Imagine the theme from The White Shark as you read the following line:

After just having recovered from ME/CFS to a large degree, I got Covid recently.

Why the dramatic music? Well, if you’re in the Long Covid or ME/CFS bubble, you know. I even had people telling me below my video, ‘Just wait ‘till you get your first serious infection again and you will be right where you left off with your symptoms’. Officially, a reinfection with Covid (I had it before) is considered a new activation of your immunological response and therefore poses a high risk for worsening your condition. It is the official guideline to ‘avoid infections’ (like, how?) to avoid long-term effects.

As you know by now, I have long since left the medical guidelines for ME/CFS (under which my recovery would not have been possible since what I did wasn’t considered a valid strategy, even less so for full recovery). I’ve come to see my body as generally recovered from the severe nervous system dysregulation it was in up until a few months ago. Which in turn means that an infection … is an infection. It happens, it sometimes sucks, it goes away.

And yet. The medical narrative around ME/CFS and how it operates under certain influences is strong. If you’ve watched any of the documentaries that are around, you’ll have seen what they say. You don’t recover. Some people get better, then they get worse again. It’s a strictly physical illness. There is no cure. So far, none of that had been true for me - but the message is strong and in the back of my mind, there was doubt. Maybe my whole ‘I’m recovering from an illness you don’t officially recover from’ was a sham? Maybe I’d eventually have to crawl in front of all of you, begging your forgiveness for spreading false hope when really I just hadn’t ‘gotten’ it yet?

So Covid came. Covid stayed for a few days. My head hurt in this specific way I only know from Covid. My chest felt tight and I was out of breath sometimes. Covid went. I continued with my life. I had to cancel two meet ups with friends that week, after which I was back to my normal activities. I’m fine.

There are two larger things at play here that I dealt with during this infection. The first is our relationship between, as I like to call it, second-hand knowledge and our own experiences. Second-hand knowledge to me is everything you can’t verify from your own experience. We rely on this type of knowledge for a lot of things in life and I’d argue that the ratio between first-hand and second-hand information in every day life is favoring the latter more and more. Just observe how much of what you’re saying every day is something you’ve actually seen first hand. Most political discussions, for instance, consist almost entirely of second-hand knowledge.

Which, to get this out of the way, isn’t bad. It’s in fact almost inevitable. The world is insanely complex and it would be impossible to navigate without relying on second-hand knowledge about how things work. I certainly wouldn’t have a bank account or a gaming PC if I wouldn’t trust something I don’t fully understand.

Trust - to a degree. My point is, we are so used to living on second-hand knowledge that we somehow completely take personal experience and agency out of the picture. Yes, sometimes we are an exact representation of a statistic, and we are just as easy to manipulate by advertising as everyone else (even though we believe we aren’t). Personal biases and cognitive fallacies are real, and second-hand knowledge helps us uncover them. That’s a good thing. But sometimes we also aren’t. And I believe we should always, always be open to that possibility.

Because, and this is the second thing, our fear response creates self-fullfilling prophecies as its main job. Fear is powerful, especially around health and other basic factors of survival. And because of its power, it directs the focus. Imagining with dread the way I was going to decline and suffer again was a sure way to get me back into a dysregulated state and put my body under more stress - which would affect the outcome of my infection as well. Micromanaging and monitoring all symptoms in an attempt to control the severity of my sickness was exactly what initially kept me stuck in ME/CFS, because it’s telling the body that I am, in fact, unsafe, and that my headache is, in fact, dangerous. As long as I believed that my brain was inflamed and taking permanent damage from my symptoms, I was fighting what I was experiencing, and it wasn’t getting better.

So I knew that even though I couldn’t ignore my doubts when I got sick with Covid, I could go through the experience calmly. Fear shouldn’t be ignored or suppressed (no emotion should be suppressed long-term, by the way, says the psychologist), but you can certainly balance it out with acceptance. I didn’t fight my Covid headache or my exhaustion, I just let it be. My body would take care of it in its own way, no need for me to focus on it intently, trying to forcibly remove it somehow.

I think our reaction to symptoms stems in large parts from our very ‘mechanical’ understanding of our bodies. We run around with the expectation that unless everything works at optimal capacity (whatever that is), we have to constantly fix things. Like, ‘Oh, I can’t be tired right now, maybe I should drink some coffee’. Or, ‘There’s this weird feeling in my chest. I want this to go away immediately.’ Everything that doesn’t scream ‘health’ signals danger to us, and we give that signal right back to the body, who’s going to respond in its own way, by, you guessed it, making it worse.

Because of this way of thinking that penetrates all areas of life, it’s often inconceivable to us to just let things happen and trust, without trying to take control. I learned to do just that in the hardest way possible this year. My biggest initial fear - that what I had was ME/CFS and that I was going to decline and be in pain for an indefinite amount of time, like a slow death - came true. The darkest thing I could think of, losing all capabilities in life but being awake enough to witness it, was happening to me to a large extent. This was darkness. And I lived through it. When I came out of it, I realized that I was no longer afraid of most things. I didn’t feel the need to intervene when something came up - pain, rejection, emotional baggage. The desire to control what happens inside and outside of myself came, in large part, from the fear of darkness - which I think ultimately is the fear of dying. But now that I had seen darkness and knew what it was like, and I was starting to befriend the aspects of it that were teaching me something, there was really not much left to fear.

Which is not at all like saying ‘I seek out every risk now because nothing can happen to me’. No. It means that whatever does happen while I’m living life is … fine somehow. The idea of control is often an illusion anyway. My experience of things, both pleasant and unpleasant, is a lot calmer and immersive now. I’m not halfway out the door as soon as something comes up. I get Covid after ME/CFS? Alright. Bring it.

I have found that the respect I’m now showing towards my body doing its thing has fundamentally changed how its communicating with me. One of the first things to learn about pain is that it’s not objective in intensity. The brain will decide, based on a number of factors, what it should look like to achieve the desired result - which is why you don’t feel the pain of your twisted ankle while running away from a predator. So now that my nervous system is regulated better and I’m actually listening when my body is signaling something, pain is a lot less present in my head when it happens. I’m not trying to fight it and it will drift in and out of consciousness a lot more as opposed to being all-consuming.

In short: After having gone through an illness that takes away all sense of agency, I now feel like I have more of it than ever before. The real power is in radical acceptance and trust, which takes fear out of the picture. I now deal with what comes up instead of fighting it to protect an imaginary future that doesn’t exist yet. I’m not asking, ‘What could happen?’, I’m asking ‘What do I need right now?’. Big difference.

So yeah, I’m doing well. Tiny house is almost fully furnished, I have settled into my routines here and I’ll be back working in props in several productions in November and maybe December. Videos on my channel continue, I’m already working on episode four of my series. Picked up guitar lessons and singing again. Life is lifing.

My recovery from ME/CFS - part five: The leap.

View from the wings during rehearsal.

If you’re new here, it is advised to read the previous parts of the series first: Prologue, Part One, Part Two, Part Three and Part Four.

It’s Saturday, October 11th, around 8:30 pm. I’m sitting on a stool on the side stage, using hot glue on a tea cup that has just come off stage and is shattered as part of the performance. The dancers are scurrying about, adjusting the fit of their pointe shoes or stretching a final time before running back on stage. The music is loud. We can actually sing along and no one notices. Lights keep changing and my colleagues in tech, props, lighting, costume and hair and make-up, all in black, are going about their business. Cues come in over the radio. It’s going well.

When I said yes to this two-week job in props a few months ago, it felt like a gamble. I had made huge progress with my recovery already, but I was still a long way from what the job would require of me. We work long hours, often in the semi-dark, carrying out time-sensitive actions from behind the scenes and interacting with dozens of people. For weeks, we often only go home to sleep and return first thing in the morning (including the weekends). It’s a work environment like no other, and one that I’ve come to love over everything else.

Like many things in my life, working in props was the result of a rather random yet decisive moment. In 2018, I had already worked as a background actress for ballet and opera for many years. I loved stage life but had little understanding of the other professions associated with it. Because we were handling machinery on stage that year, us dancers and background actors were working with the tech department more, and I got curious. I had just completed my tiny house build so for the first time, some of the things they were doing seemed familiar to me.

Come closing night, the whole production wrapped up in the feeling of success and sipping away on sparkling wine before everyone went their respective ways, I saw the stage tech team leader prepare to leave. On a whim, I walked up to him and asked: ‘So … if I wanted to work in your department, what would I need to do?’

In my mind, this was a far stretch. I had no working experience or formal training in the field and this wasn’t exactly a small-town theater. There was also, to my knowledge, only one woman on the team and I was by far the youngest. I don’t even know if he reliably knew my name then. But I went and asked anyway. Three months later I was testing out in stage tech and three months after that I moved to props. This year, despite the circumstances, I became the senior props manager for a large opera production with the Berlin Philharmonics, and I will resume that role for next year.

Everyone who knows me personally will tell you how my eyes light up when I talk about work. It’s an incredibly vibrant, intense environment and you meet the most extraordinary people. Dozens, sometimes hundreds of people coming together to produce the best version of an opera, a concert or a dance performance that they can create - there’s just nothing quite like it.

During my time with this illness and throughout the recovery, a big part was being able to let go of my previous life. There were definitely some things, patterns, people I had to say good bye to in order to move on. Since I didn’t know if I was ever going to be truly getting better, it was important not to cling to jobs or activities and be eternally upset that I couldn’t do them anymore. I simply didn’t have the energy for it.

At the same time, I also knew that simply ‘giving up’ wasn’t going to do the trick either. I had to find a way to imagine a life after illness that consisted of things I truly loved, even if they felt unattainable at the time. And stage life was definitely a big part of it. So when the offer came in, I decided to say yes, even if in that moment, it was impossible to say whether I could actually do it.

Over the course of the summer, I did indeed make a lot of progress in my recovery, but up until a few weeks before my previous post, I also felt slightly stuck, like I had hit a ceiling. Which, after a while, makes you go: ‘Maybe this is as far as I’m going to get.’ It was certainly nowhere near the ability to work overtime for two weeks straight.

A few days before I went to work, my parents had friends over from the US and we spend a lot of time together, which was the first time in my recovery that I was with several people for more than an hour or two. It went well, sometimes I had to take a break but I was even able to go on a little hike with them the final day. (Again, first time in about a year.) I had a bit of brain burn and some fatigue, but I felt good.

So when I eventually did go back to work, an interesting thing happened. This was it. I was going all out. No hypervigilance, no slow introduction into the new activities - just … bam. And it worked. At this stage, my engine had been back up running a little bit; sputtering still, but technically intact. I knew, even though it didn’t always feel like it, that based on my level of activity now, there was no reason to believe that there were any physical limitations. If anything, it was my nervous system still catching up. So I went from an average of 1,500 steps in September to 13,000 on my third work day. It was like I kicked the engine and the sputtering stopped - instead, it was running just like it used to. A little tired sometimes but otherwise fine.

There is a line that kept coming up in recovery interviews I had watched in spring - ‘At some point, you have to start living your life again’. To someone who’s bedbound and unable to feed themselves, this obviously sounds like a trivializing insult, but it’s not meant for this stage of recovery. Instead, speaking from my own experience, it’s a crucial piece of advice for this period of transition when you’re coming out of the ‘chronically and severely ill’ phase into the ‘somewhat recovered? Maybe better? Where am I?’ phase. A lot of people, judging from the countless interviews I watched, get stuck when they’re, like, 70 or 80 percent there, and it seems like there’s a reason for this plateau.

As with most things in life, I tend to favor a psychological perspective (humor me, it’s my degree after all). When I started working on my recovery and all these small things started returning to my life - reading a few pages, being able to take out the trash, gaming for an hour or two, even when it came with some symptoms - it obviously felt like win after win. I was on a slow and almost steady roll. Yes, there were ‘relapses’ in between (again, I think ‘adjustment period’ is a more accurate description) but they became fewer and fewer.

As you expand your range of activities over time from house-centered to outdoors and social activities, the individual steps will naturally get bigger. It’s simple to go from reading two pages to reading five, and you can stop at any time. But the leap from not leaving the house to going to a store is much bigger, and at some point, it doesn’t make much sense or is impossible to ‘portion’ these things. Like, I’m either going to go to the movies or I’m not. I don’t want to walk out during the film just so I ‘gradually’ get used to this activity again (even though it’s important to remember that I could, at all times, do exactly that).

So as time goes on, the acts of courage while rebuilding your life will get bigger and bigger. And at the same time, you realize you’re no longer at the very bottom. Id est, you have things to lose. So naturally, you start to bargain. Like ‘Maybe I’m going to rest a little, just in case, because I don’t want to be in pain again’. And so I was teaching myself that some things weren’t ‘safe’ enough yet.

Sure, part of it is plain acclimatization, and I used that whenever I could. I probably could have been on that hike in July, physically speaking. But I wouldn’t have felt up for it. So giving myself time was crucial. But at some point, and I quote, ‘You have to start living your life again’. Pre-emptive rest, monitoring of symptoms around certain activities and ‘micro-dosing’ life eventually kept me stuck.

There is also a different component to it. When dealing with a mainly psychosomatic illness, we understand during recovery that something (often multiple things) in our previous lives has made us sick. We have, maybe for the first time ever, experienced true rest and freedom of some of our responsibilities. As we’re moving towards recovery, ‘life will continue’ can seem like a threat rather than a relief. Since a lot of my time resting had been spent in various levels of pain and exhaustion, I hadn’t yet made up my mind about all aspects of my future life. Naturally, it seems daunting to transition back into the responsibility to sustain yourself financially (I had been on sick benefits), to run a full household and to kickstart a social life that had been pretty much non-existent for many months. Plus, as many will experience after life-threatening or otherwise severe illness, a lot of things simply don’t seem the same anymore - you’re not simply returning, you sometimes pretty much start from scratch.

So as I moved along my recovery, the big leap back into a ‘full’ life seemed daunting and overwhelming for a long time. Yes, you can chop some things up into smaller pieces - if you’re employed, you can return to work with fewer hours initially, for example - but there will always be a few big, binary chunks. Either you’re doing them or you’re not.

Part of that is also people’s assumptions. Seeing me go to work will alter their expectations of me - something I have been very mindful of from the beginning. I attended my choir’s concert on the weekend and upon hearing how I was doing, they all hoped to see me back in rehearsal in a few weeks. To which I replied, I can’t tell you yet. I will make that decision in my own time.

As I was sitting there on the side stage, fixing the cup that inevitable would get smashed on the floor again in the next performance, I was beaming. All the introspection and the hard mental and emotional work I had put into my recovery was worth it ten times for this moment. I now remembered what it felt like to be alive. And it was the most extraordinary feeling.

My final day of work for this project was ten days ago. I neither crashed during nor after, I still experience fatigue and a bit of brain burn sometimes, but that’s it for now. The shows went well, I met lovely people along the way and I’m back at the opera in a few weeks for a new production. Knowing that I was able to pull off a big job like this one without having to push myself physically or mentally, and knowing how much I enjoyed that, builds a lot of confidence. I have since moved back into my tiny house permanently and am renovating the final bits as I go.

And yet, I don’t make haste. Pressure is a big thing in healing from anything, so I’m not saying ‘I’m now fully recovered’. There are still some leaps ahead of me I’m sure. All I’m saying is I made it very far and I’m in a good place right now, and time will tell the rest.

My recovery from ME/CFS - part four: bends in the road

If you clicked on this after Sunday, September 28, there’s about a 75 % chance you got here because of my YouTube video. If you’re struggling with English, your browser likely has an in-built translate function somewhere. And in case you haven’t done so, you should read the previous parts of the series first: prologue, part one, part two, part three.

I thought about this next part for many weeks. I feel like now is the time where we leave chronology behind. It doesn’t make sense to guide you through every bend in the road I experienced during the now six months of my recovery up to this point - not that I would even remember all of them anyway. Instead, I now want to focus on some of the things that I learned, acting as tent poles during this crazy storm. As always, these things were true for me, they don’t have to necessarily be true for you - although I have a hunch that many others can relate. This post will be somewhat darker than usual (not exclusively dark though), but just as important.

Let’s start off by acknowledging that either way you go about ‘recovery’ (more on this idea further down), it is probably the hardest thing you’ve ever done. So naturally, you will become extremely fed up and desperate with it at some point. I certainly did. Many, many times. I think especially when you’ve been through shit time and again, health-wise and mentally, and each challenge seemed to be harder than the one before, you ultimately ask yourself: Where is this going to go? And am I maybe, just maybe fucking my life up on purpose? I mean - and I was never inclined to think like that before - no one deserves the level of suffering you go through on a daily basis with an illness like ME/CFS. No one. And just for the record, guilt-tripping doesn’t help either.

This is fear. It’s the fear of having seen darkness and knowing it can come back. It’s the fear of reaching a point in time where you will no longer be able to bear darkness. I think it’s one of the most central issues in any life-altering event or process, and I have returned to it many times, which is why I’m addressing it here. No sugarcoating - there are moments where you simply do not want to exist, and you do wonder if there will come a time when you will try to facilitate that non-existence yourself. Suicide among ME/CFS patients is well-documented.

The human body and brain have an astounding capacity for handling daily pain. It’s the mind (and, if you believe in that, the soul) where the long-term effects show up much sooner. For me, a couple of things have happened around that issue over time and I’m not yet ready to share all of them here - some will take a lot of explaining anyways. But here’s part of what helped me not succumb.

First of all, I think many of us have very little social context for darkness because society practically doesn’t address it. A lot of us, in the context of trauma or other experiences, ultimately know what it’s like to feel logic, physics, personalities and reality itself bend and dissolve in front of your eyes because either you are in too much pain for these things to still make sense or you have been exposed to events that are so horrible that there is no way to connect them to the world you know. I’ve seen both. But until trauma therapy, I had absolutely no one to relate to over these experiences. With the following effects:

Any experience of ‘falling out of the world’, as I put it in my younger years, was incredibly isolating. Because I couldn’t talk to anyone about it, it also had no language. Which made it even more frightening. And because it didn’t seem normal and it came with all this intense discomfort, I did everything in my power to stay away from it, fearing it might lead to … well, who was to say?

In any case, staying away didn’t work. ME/CFS has a lot of darkness-inducing elements. Your perception is altered or dampened, your physical abilities reduced in this weird, inexplicable way, you often experience the dread of not being able to escape your own body with all these intense symptoms. And you’re being told by medical professionals that this is now your life.

In some sense, that’s true - living with the illness, even if you then recover, is your life for a long time. So in order to not dissociate all the time, I had to find a way to integrate darkness into reality. Ordo a chao. I researched, talked to my therapist and found some answers for myself. For instance, darkness is normal. It’s a normal response to circumstances that don’t match anything you’ve previously seen. For me, the first conscious memory of this acid-like feeling in my whole body was when I witnessed a roused cow violently attack a drunk civilian in an arena, to the (apparent) bloodlusty pleasure of the onlookers. I remember how limp the man’s body looked as the cow was thrashing it against the ground. He was carried away on a stretcher and I don’t know what happened to him. I was still a kid and the experience horrified me intensely. None of it seemed to make sense in the world that I had thought I was living in.

So, darkness as a response is normal. And in order to establish this normalcy to your nervous system, you have to talk about it. During my recovery with ME/CFS, I kept a ‘burn after reading’ journal, meaning it was a place where I was brutally honest in sharing the feelings I had in that very moment, even if I deemed them ‘irrational’. Experiences of reality-bending darkness, induced by long stretches of brain burn (as I still like to call it) or ongoing fatigue, were a common topic. I was allowed to express how upset I was about that. I didn’t have to put on a rational, brave face. And if I didn’t want to exist in that moment, I also said that. It was liberating and it brought all these things into the light and out of shame.

Again, this is only my own reasoning here, but I realized that making it okay to feel like I didn’t want to exist sometimes, because of what I was going through, was already taking away a lot from that wish. I mean, it’s not that I wanted to be dead, I just didn’t know how to handle that kind of life. And part of the answer for me was to make nothing off-limits. There can be no taboos in an existential situation like this one.

The other thing, and that’s maybe even more difficult to explain, is that I’ve found that even darkness is less dark when you are able to understand it better. I have had the same experience with fear, which is an emotion I tried to avoid rigorously for a long time, thanks to my panic attacks. It was only during the last few months that I started to integrate and see it as a normal emotion that, slowly, over time, you can sit with and learn about.

The same applied to darkness. Up until recently, I was convinced that in order to stay ‘sane’, I couldn’t sit with darkness too much (classic fear response). Which obviously resulted in me always being on the lookout for darkness and making sure it stayed away. Which is called hypervigilance and exactly the type of thing we don’t want when our nervous system is dysregulated. Instead, I now slowly start to lean into it for a while. In order for it to not consume me, I had to start looking at it with curiosity. I know this can be confusing for anyone who’s not familiar with therapeutic concepts but this has been backed up by my own therapist and many more and it was an incredible relief to know that there is a process for this - other than trying to ignore something like this for forever.

This is a difficult topic because this type of work, in my mind, requires professional help. At the same time, not bringing it up here and sharing how I dealt with it would be a disservice because it was and is a crucial part of my recovery - and not everyone always gets the professional help they need, for various reasons. So stating here that even something like profound inner darkness can be dealt with is important. And simply saying ‘if you feel depressed, go see your therapist about it’ creates an exclusiveness around this information that certainly didn’t serve me when I was in that situation.

Another thing that ties into this that I have to mention at this point is recovery as a concept itself. You can’t imagine the relief when you hear someone else’s story for the first time and the idea of getting out of that illness becomes a possibility all of a sudden - only to then be backed up by hundreds more of these stories. I don’t know if I would have done any of this hard work if I hadn’t seen it take effect in others. You lose your trust many times over.

But. As exciting as it is to see people speak of themselves as ‘100 % recovered’ (and I have no reason to doubt their stories), it will eventually create a certain pressure to get there yourself. No matter how much you try to avoid it, you create a timeline in your head. In my case, after listening to about twenty different recovery interviews, my vague hope was that I was going to be able to recover within maybe four months. Which, on the one hand, was amazing because that felt like a manageable timeframe. If my estimate would have been years, I don’t know what I would have done. However, I realized after about three months of recovery I was starting to get stressed out because, although I had made it far, I wasn’t ‘there’.